In water-rich Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) taps often run dry. As the third most populous province in Pakistan, KP is grappling with complex water management and governance challenges despite having abundant water resources. The region faces a significant level of multidimensional poverty.

Seventeen percent of households lack access to improved drinking water sources, such as household connections and public standpipes, which are designed to protect water from outside contamination. Agricultural water productivity is also low, with 50% of water lost at the field level. Approximately 1.8 million people are reported to be at risk of health issues due to recurring floods and declining water quality.

Urbanization and population growth, combined with climate change and mismanagement, have made water governance in the province a critical challenge. Despite policy mandates, local communities in Pakistan have little say in water governance. While the 2018 National Water Policy highlights the importance of stakeholder participation at all levels, local communities remain excluded from decision-making processes.

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Water Act of 2020 was enacted to provide a comprehensive framework for the regulation, allocation and protection of water resources. While it strengthens administrative control over water resources, it neglects to provide a legal mechanism for community engagement — without which the Water Act falls short of ensuring inclusive water governance.

Evidence-based insights to closing water governance gaps

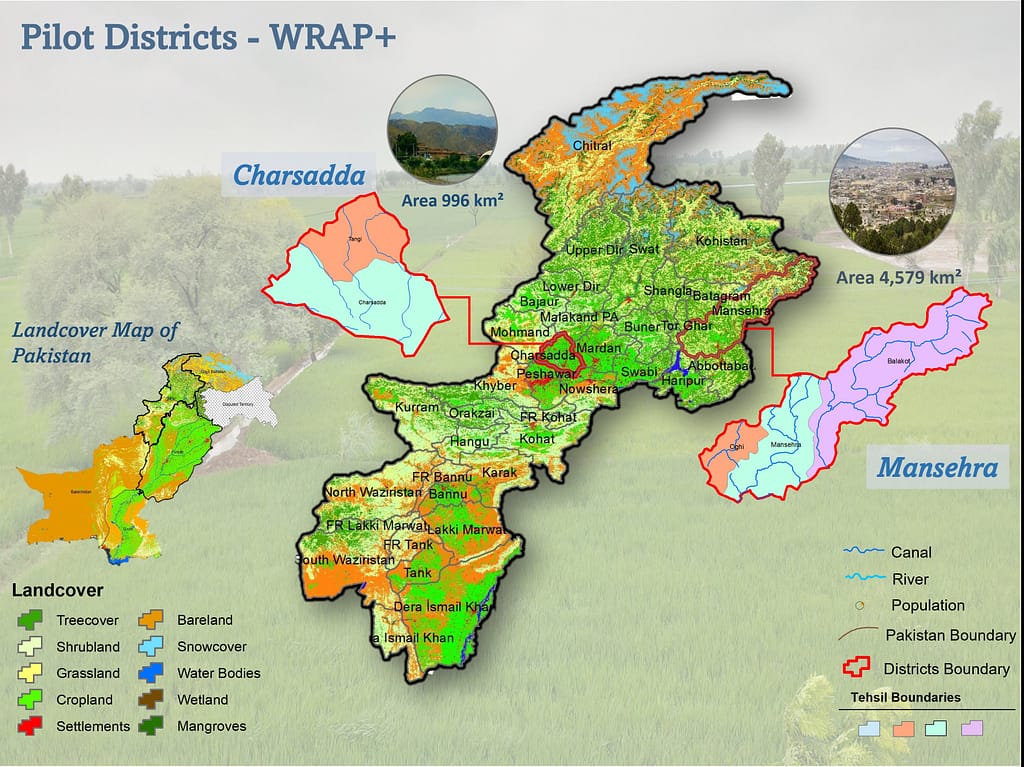

The International Water Management Institute (IWMI) has stepped in to build the capacity of water departments at both the provincial and district levels in KP, guided by community priorities. This work is undertaken as part of the Water Resource Accountability in Pakistan (WRAP) Program funded by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). IWMI is guiding the implementation of the Water Act 2020 in the pilot districts of Charsadda and Mansehra and supporting the alignment of policy with ground realities.

To understand existing conditions and community perspectives, IWMI conducted a baseline survey of 1,188 households from the pilot districts. The survey examined community perceptions of current water systems, focusing on trust, accountability, transparency and adaptability.

Key findings indicate that public confidence in water governance systems is low. There is a clear disconnect between public services in Charsadda and Mansehra and the lived experiences of local communities.

Accountability mechanisms are poorly understood, and transparency emerged as a major concern across both districts.The majority of those surveyed said they were unsure about how decisions regarding water management are determined, or who to reach out to if they have concerns. However, trust in public water services varies between the districts. While 84% of respondents in Mansehra distrusted the system, only one in four respondents from Charsadda reported the same.

Public awareness of water and sanitation issues remain low across both districts, further exacerbated by limited grassroots engagement. Few community-based organizations or informal groups exist to advocate for water and sanitation concerns.

On a positive note, access to water is generally perceived as equitable within the community for women and children. However, community members feel more can be done to fulfil the needs of persons with disabilities.

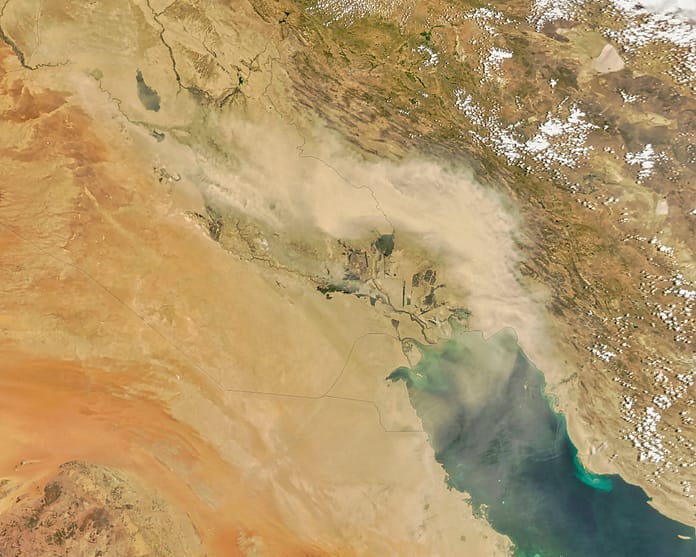

A major concern that emerged was the perceived inability of local water institutions to adapt in times of crisis. Most respondents doubted the capacity of public services to manage emergencies effectively — a gap made even more alarming by the ongoing floods that continue to test Pakistan’s strained water systems.

Informed by these findings, IWMI will guide local governments towards evidence-based decision-making in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, by co-developing practical tools and solutions to strengthen institutional capacity and improve water governance.

Actionable strategies to engage community members in water governance

Pakistan is moving ever closer towards a severe water crisis driven by climate change, outdated infrastructure and decades of institutional inefficiency. Weak water resource planning and poor data management have further deepened this crisis. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) argues that water crises are, at their core, crises of governance — a view echoed by growing global research showing that water security depends on effective management and equitable allocation of resources.

As seen in Thailand and India, when communities are involved, they contribute to solutions that deliver tangible results. In Thailand, community action has helped reduce groundwater salinity, while in India, citizen science guides groundwater allocation. Effective water governance depends on accountability, transparency and trust, which must be upheld across national, regional, community and household levels. Given the complex, uncertain and multi-dimensional nature of water challenges, water governance must be both adaptive and grounded in local knowledge.

Community participation must be the new cornerstone of effective and equitable water governance in KP. Local water authorities must create opportunities for communication by establishing formal and informal consultation channels. There is also a need to harness digital and community-based tools to increase transparency. Low-cost digital tools such as SMS notifications and WhatsApp groups can be used to update farmers on groundwater availability, water quality and irrigation demand management. At the same time, women and marginalized groups must be included in Village Water Committees or Water User Associations for equitable decision-making.

Finally, long-term progress depends on promoting inclusive knowledge and capacity building. Community education in local languages, social media and popular mass media channels can be used to spread vital information, rebuild trust in water systems and connect scientific findings with the wider public. Citizen science initiatives can empower communities to monitor water access, quality and usage, while co-producing knowledge that contributes to transparent, inclusive water governance.

Without these systemic shifts, policies remain disconnected from the lived experiences of those most impacted, undermining long-term water security and resilience.