The United Nations (UN) has declared a state of global water bankruptcy, pointing to widening gaps in who gets access to safe water and who is left out. The report published this January leaves little doubt that correcting the world’s water deficit requires fundamental shifts rooted in water justice.

Responding to the water crisis means treating water justice as a governing principle, one that moves beyond simple efficiency to restructuring systems — so all people and nature can access water safely and fairly. Incremental gains in efficiency, financing and technical solutions are no longer sufficient; the course correction required has to be transformational.

Water justice can mean different things to different people. For governments, water justice is embedded in the legal frameworks for the proportional and fair distribution of water. For communities, it is the lived experience of navigating water scarcity, exclusion and risk. While some emphasize the fair allocation of water for all users, others focus on safe access for households. Many want a balance between human needs and ecological flows.

At its core, water justice encompasses the ethical and equitable redistribution of water resources and benefits. This includes embracing diversity while acknowledging and responding to historic legacies of injustice. To achieve water justice, we must move towards restorative and transformative processes that enable informed and proportional participation of all water users in decision-making processes. This understanding of water justice extends beyond humans to encompass water and all the life it supports.

Water justice is essential because it serves as a barometer, measuring whether water is shared equitably, without bankrupting its availability for people or nature.

Water justice, who is it for?

Water injustice is profoundly local and experienced every day. Research shows that it mirrors various forms of discrimination, such as gender, caste- or ethnicity-based exclusion, income inequality and unequal gender-labor burdens. It manifests in who gets excluded from water supply systems. Communities living in informal settlements in Jakarta, Indonesia, deemed “too poor to be profitable,” have little to no access to municipal water. Women living in the slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh, struggle daily to collect water at the mercy of informal water tankers, often paying more than their affluent neighbors.

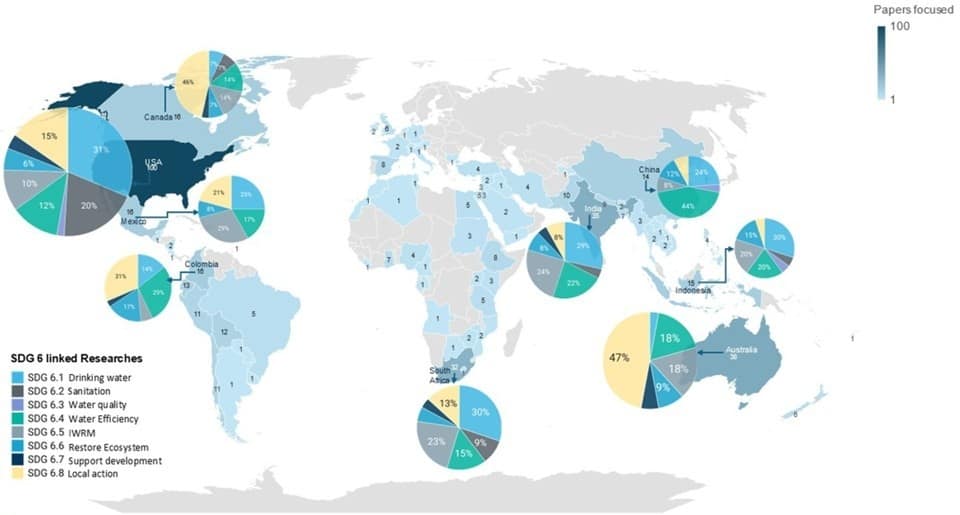

This intersectionality cuts across both the developed and developing world. No one is immune; even in high-income economies, structural inequalities can remain hidden behind aggregate data. For example, First Nations communities in Canada face acute water scarcity; in Flint, Michigan, United States, families of color confront health risks stemming from systemic exclusion from safe drinking water; and in remote regions of Australia drinking water quality remains a persistent challenge.

Justice also crosses boundaries and sectors, demanding attention to how resources are shared at the basin scale. From transboundary river development to urban water expansion that can undermine neighboring rural communities, each scale presents distinct challenges that cannot be aggregated or addressed in isolation.

The experiences of injustice are not purely a failure of institutions, but rather the lack of proper attention to the social constructs that shape the systems within which we operate. Achieving justice requires centering people and institutions within collaborative rather than competitive structures.

What does reaching for water justice look like?

To ensure transformational processes for water justice, there needs to be a sustained, conscious and collective effort. It is an iterative and ongoing journey, already underway in many parts of the world.

Each intervention that is part of this journey should respond to three questions: Who benefits? Who decides? Who bears the costs?

In practice, advancing water justice often means strengthening local capacity and shifting decision-making powers to the communities most affected. This is achieved by institutionalizing transparent, multi-stakeholder platforms dedicated to shared water planning and knowledge creation. For example, the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) collaborated with local government to establish such a platform in Nepal’s Barahathawa Municipality. Where they brought together farmers, water users, government officials and local leaders to jointly manage groundwater resources and address interconnected agricultural challenges.

In South Asia, 71% of women in the labor force work in agriculture compared to 41% of men, yet despite this substantial presence, women remain largely excluded from formal water governance decisions. For true water justice to be achieved, women and marginalized groups must be supported to be part of and lead within these platforms. This change is gradually taking place in parts of India and Nepal with more women participating in decisions on agricultural water use.

There is also growing recognition of the plurality of knowledge systems and water-values, including indigenous, cultural and ecological rights. These diverse perspectives are increasingly being integrated into participatory water conservation efforts aimed at protecting and restoring water sources.

Achieving water justice also requires interconnection between systems such as water, energy, food and the environment (WEFE), for pragmatic conservation effects that balance water use, nature and development. IWMI’s work in Africa demonstrates this approach in practice, showing how integrated green-grey infrastructure systems achieved superior climate resilience and inclusive economic growth when designed through WEFE nexus planning that harmonizes policies across sectors and actively engages marginalized communities in decisions on resource allocation.

Finally, we must measure progress openly, learn together, and share accountability between state and society.

Reaching for water justice requires us to accept that there are no perfect solutions. Neither can we wait for the perfect time to start. Integrated policies that center justice are an important step, but we must be mindful not to get trapped in the use of buzzwords alone. The antidote is to center communities, invest in co-governance and align technical solutions with institutions that prioritize collaboration, equity and care.