Under the sharp winter sun in the remote village of Chimkatola, India, Pushpa Devi stands beside a humming solar-powered rice mill as she explains to visiting researchers and policymakers how women in her village transformed their access to irrigation and local rice processing.

The International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and partners introduced solar-powered irrigation pumps and rice mills to farmers in the villages of Chimkatola and Kevlari in Madhya Pradesh, India, in 2024. A little over a year later, these villagers are proving that clean energy can be a pathway to economic empowerment and climate resilience.

This South-South learning exchange was facilitated in partnership with the local nonprofit organization Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN) under the IWMI Solar Energy for Agricultural Resilience (SoLAR) project. Researchers and policymakers from Kenya, Ethiopia, Bangladesh and India interacted with Pushpa Devi and other women farmers, learning how solar-powered rice mill machines and solar irrigation pumps reshaped their daily lives.

“Kenya’s irrigation potential is 3.3 million acres, yet only about 710,000 acres are currently under irrigation. Seeing women in rural India operate solar pumps and collectively manage irrigation revenues is a powerful example for us,” said the Irrigation Secretary of the Ministry of Water, Sanitation and Irrigation in Kenya, Vincent Kabuti. “As Kenya expands solar solutions for smallholder irrigation, this model demonstrates that when communities, especially women, take leadership, irrigation systems become more accountable, efficient and sustainable.”

The South–South learning exchange gave the delegation a close look at how flexible financing is accelerating solar irrigation, how surplus power is being channeled into rice milling, and how combining solar generation with farming on the same land can more than double farmers’ incomes.

Flexible financing for solar irrigation draws more women from Kevlari and Chimkatola into agriculture

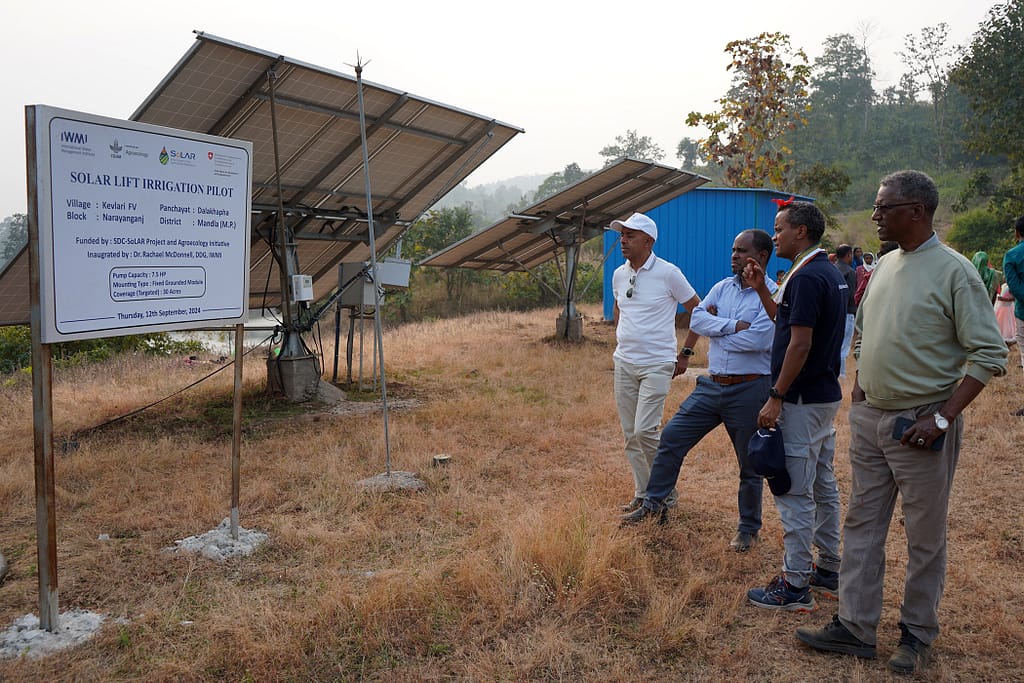

In Kevlari, two complementary community-led interventions were implemented to strengthen women’s livelihoods and local value chains.

The first was a community-based Solar Irrigation Pump (SIP) model, benefiting 13 women farmers. In this model, all initial capital investments of installing SIPs were covered by the Swiss Agency for Cooperation and Development (SDC)-funded IWMI SoLAR project. This ensured that financial barriers did not prevent women farmers from accessing irrigation pumps and adopting climate-resilient farming practices. Responsibility for the SIP system was subsequently handed over to the women-led Water User Associations (WUA), who manage its pump operations, water allocation and revenue.

The second was a community-operated semi-automatic rice milling machine, powered by unused solar energy generated by the SIP. Unlike with the SIPs, farmers contributed INR 10,000 ($110) as an upfront payment towards establishing the rice mill. Of the total INR 90,000 ($992) cost for the mill the IWMI SoLAR project covered INR 55,000 ($606), while the remaining INR 25,000 ($276) was accessed through a cash credit loan under the State Rural Livelihoods Mission (SRLM) government initiative. The solar-powered rice mill allowed the community to process paddy locally — saving time and money.

In neighboring Chimkatola village, a slightly different model was implemented. Here, the community contributed to upfront installation costs of both the SIPs and rice mill, while a revolving fund reinvested earnings into new agricultural technologies. As in Kevlari, women-led Water User Associations operated shared Solar Irrigation Pumps (SIPs) and a community-run solar-powered rice mill. But Chimkatola farmers contributed 10% of the total installation cost to the SIPs, while the remaining 90% was covered by IWMI’s SoLAR project.

“Initially, women were hesitant because some investment was required. But once they saw the benefits, their confidence grew. Today, more farmers are using the rice mill and accessing irrigation water from the solar pump,” said Pushpa Devi, who is also a member of the Chimkatola WUA.

Here too, the community-operated semi-automatic rice mill was established by utilizing unused solar energy generated by the SIP. The upfront cost of the rice mill — which was of the same value as in Kevlari — was shared among the farmers, IWMI’s SoLAR project and a cash credit loan under SRLM.

“The contrast between the two villages highlights how flexible financing can empower communities in different but equally meaningful ways,” said Darshini Ravindranath, Senior Researcher at IWMI.

WUAs made up entirely of women were trained in governance, financial management and the technical operation of solar infrastructure. Both groups maintain dedicated bank accounts and have established transparent systems to manage irrigation revenue. These shared community resources, managed by women-led groups, have reinforced collective ownership, energy efficiency and livelihood enhancement in the villages of Kevlari and Chimkatola.

“In both villages, a significant change was observed among women farmers. Those who were initially hesitant to take bank loans for solar irrigation later came forward with confidence, taking loans and paying upfront costs to adopt solar rice mills,” said Deepak Varshney, regional researcher at IWMI. “This demonstrates that with even a small push — through flexible financing and initial support — farmers are ready to move away from traditional practices and embrace solar energy for agricultural use.”

Land-efficient renewable energy linked to 168% jump in earnings

Following the field visit to Kevlari and Chimkatola, the delegation visited a privately owned agrivoltaics (APV) site at the Indian Council of Agricultural Research in Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Ujwa, Southwest Delhi. The APV land-use approach combines agriculture and solar power generation on the same piece of land, allowing crops to be grown while solar panels generate electricity above or alongside them.

Launched in 2021, the Ujwa agrivoltaics system has been successfully growing crops such as fenugreek, coriander, cauliflower, okra and leafy vegetables under its 110 kilowatt-peak (kWp) solar power system.

While agriculture under APV shade yields slightly lower returns, equivalent to INR 150,000 ($ 1,600) per acre compared to open fields, the additional income from selling solar power generation is around INR 360,000 ($3,900) per acre per year. Marking an impressive 168% rise in total annual income per acre, equivalent to INR 510,000 ($5,500). With 70% of income derived from solar power and 30% from crops, the model illustrates how agrivoltaics can significantly enhance smallholder incomes while sustaining agricultural productivity.

“The agrivoltaics demonstration shows how land can be used wisely, producing both energy and food without compromising productivity. For Ethiopia, where land and water pressures are increasing, this model offers a powerful blueprint for integrating renewable energy into agricultural systems,” said Elias Awol, CEO, Smallholder Irrigation Development, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of Ethiopia.

As countries across East Africa and South Asia scale up solar irrigation, the lessons from pilot sites in India underscore that technology alone is not enough — institutional design, women’s leadership and financial inclusivity are equally critical. IWMI will continue strengthening South–South collaboration to test, refine and adapt community-owned energy models across diverse contexts. Focusing on deepening research on productive solar uses, expanding women-led water governance structures and co-developing financing pathways that suit smallholders’ realities.