On one corner of my desk at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) office in Egypt sits a tiny succulent. It is a pretty plant with wide green leaves, and to most, it is just a splash of life on a busy desk filled with water models and data analytics. But for me, it has become a laboratory for testing smart irrigation ideas on a miniature scale.

Like many others who lack green thumbs, I once watered my plant whenever I remembered. Sometimes too much, leaving the soil soggy; other times, too little, especially when I was away on field work or leave. The result was a stressed plant and wasted water. My inconsistency mirrors what happens in water management on a much larger scale across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: low efficiency and staggering waste amid severe water scarcity.

From a potted plant to hectares of fields

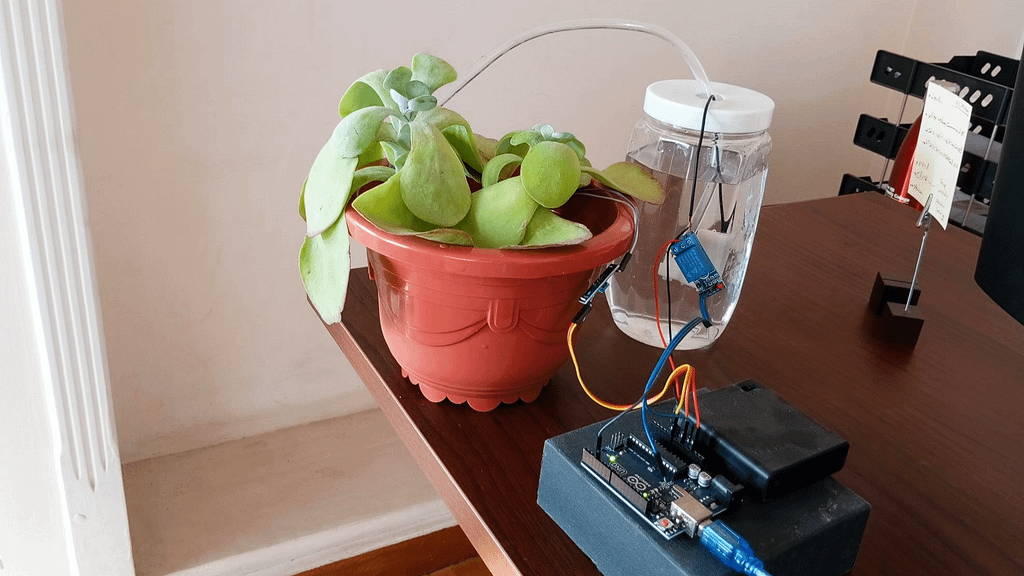

For the tiny plant on my desk, I built a simple fix. An automated irrigation system, built of a soil moisture sensor, an Arduino board and a tiny water pump — all wired together and powered by a few lines of code. The system monitors soil moisture and waters the plant only when necessary. After some trial and error to find the right thresholds, it now runs perfectly: no overwatering, no thirst and no worries when I am away. My little succulent drinks only on demand, no more, no less.

My little plant provides a lesson far beyond my desk and pushes me to rethink how we use water as a region. Agriculture in MENA consumes on average nearly 85% of available water, and the region’s irrigation efficiency remains among the lowest in the world. Much of the water is lost to evaporation, runoff and improper use at the wrong time or in the wrong quantity. Imagine pouring so much water that it overflows the pot and spills across the desk — except multiplied by thousands of hectares.

If farmers adopt systems that irrigate on demand, for example through soil moisture sensors, remote sensing data and responsible solar irrigation, linked with smart irrigation scheduling and precision water application, they could significantly reduce water losses while maintaining or even boosting yields. In Pakistan’s Chakwal region, farmers using IWMI’s real-time soil moisture sensors have increased crop yields while cutting irrigation costs and conserving water. The sensors’ simple color-coded alerts help farmers irrigate only when needed, reducing both overuse and waste. In India, IWMI’s SoLAR project is helping farmers shift from pumping more groundwater to saving it by rewarding conservation instead of extraction. This approach links solar-powered irrigation with sustainable water use, supporting a more groundwater-aware farming system.

The same principle of efficiency extends to factories, cities and households. Industries that use water to cool machinery, clean products or process food can recycle water instead of discarding it. For example, in Morocco and Egypt, IWMI is helping governments measure the costs and benefits of water reuse and pilot safe, efficient reuse systems that can scale from factories to cities. Furthermore, urban utilities can fix leaks that often lose a third of the supplied water before it even reaches taps. Households can adopt smart meters or low-flow fixtures.

Each of these actions is the industrial or urban equivalent of my Arduino smart irrigation system, matching supply with actual demand instead of relying on wasteful guesswork.

A smarter water future

Water scarcity in MENA will only deepen with climate change and population growth. Solutions must come from every level, from regional policies and governance to farms, communities and office desks. Water efficiency is an essential strategy for sustaining water access. Efficiency is not about sacrifice: it is about ingenuity and making every drop count.

My mini irrigation system is a simple reminder that technology, even at its tiniest scale, can drive real change. I am looking at my thriving desk plant and imagining the collective impact of smart irrigation on farms of thousands of hectares, cities of millions of people and industries using thousands of liters of water.

From my plant experiment emerges a broader understanding of water scarcity and waste, and the belief that solutions can start anywhere, at any scale and by anyone.