Ten months after launching its landmark report, the Global Commission on the Economics of Water — together with its convenors, including the Government of the Netherlands and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) — will return to World Water Week to reflect on the momentum it has generated, the pushbacks it has faced, and the path ahead. The discussion will explore how we can govern the hydrological cycle as a global common good and deliver systemic transformations. Join the conversation in Stockholm or online on August 27.

The launch of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water

In the lead-up to the 2023 UN Water Conference, the Government of the Netherlands convened the Global Commission on the Economics of Water. Its purpose was clear: to spark global debate and mobilize action on the world’s escalating water crises. As Henk Ovink, Executive Director of the Global Commission, explained: “Using the momentum of the 2023 UN Water Conference, inspired by the economic reviews on climate and biodiversity by Nick Stern and Partha Dasgupta, and from the conviction that we needed to look at the economy through a water lens, building on years of working on valuing water and pushing water higher up the societal, business, finance, public and political agendas, at every scale and in every context.”

The Global Commission’s deliberations led to a number of key findings, including:

- Water, climate, and biodiversity are inseparable: Progress on one depends on progress on all.

- Land use — conservation and restoration — is as critical as water management: It can either protect or destabilize the water cycle.

- Green water matters: Rainfall stored in soils and flowing through plants is half the foundation of a stable water cycle, yet it is largely absent from policy and economic debates.

- Water justice must be central: Fair governance means setting just water limits, meeting basic needs, and addressing inequality.

- Accelerated action makes economic sense: Urgency can unlock incentives for further action.

- Financial and economic actors hold critical levers: They can resolve water crises in ways traditional water managers cannot.

- Economic incentives must align at all levels: Micro- and macro-level decisions often pull in different directions.

These insights are captured in the Commission’s final report, “The Economics of Water: Valuing the Hydrological Cycle as a Global Common Good.” More than a policy paper, it is a starting point for debate and a call to action. By reframing how we understand, value, and justly govern the water cycle, the report aims to shift priorities, change investments, and inspire systemic transformation.

“The Global Commission on the Economics of Water was a unique and timely attempt to bring the economics of water to the forefront of global discourse. It created a rare opportunity to be part of a diverse ecosystem, yet work collectively towards a shared goal: restoring water as a critical economic resource in national and global priorities.”

Arunabha Ghosh, CEO, Council on Energy, Environment and Water

A hydrological cycle framework

“A water cycle perspective broadens the scope of integrating both blue and green water, spanning the full development agenda.”

Henk Ovink, Executive Director of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water

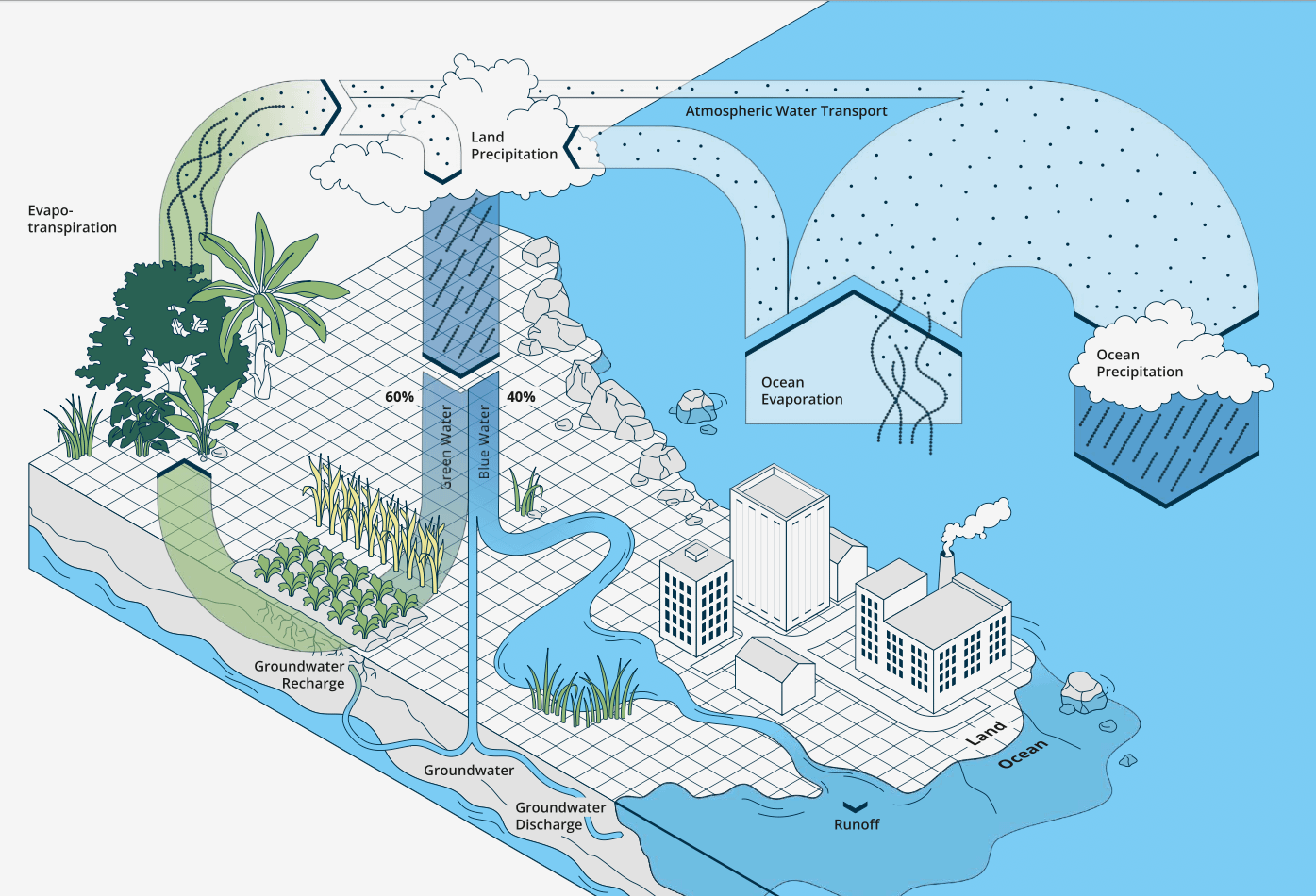

Water is far more than rivers, lakes, and oceans. The Global Commission captures its full complexity through a comprehensive hydrological cycle framework that links three interconnected domains: blue water (liquid water in rivers, lakes, and aquifers), green water (soil moisture and evapotranspiration), and atmospheric water (water vapor and precipitation).

The framework highlights both the human drivers that disrupt this cycle — such as land and water mismanagement, poor climate action (both mitigation and adaptation), trade imbalances, inequitable access, disruptive subsidies (undermining water security), and inadequate (if at all) pricing — and the relevant actors who shape it. These include managers of green and atmospheric water, whose decisions can profoundly influence the water cycle, but who often do not see themselves as water managers, and are rarely recognized as such by traditional blue water managers. This lack of recognition is reinforced by the absence of explicit attribution of green water and the broader water cycle in policies, regulations and governance approaches.

The cost of inaction

“Inaction will make economies head toward a cliff that becomes higher every year, with fewer options to change direction, and less prospect of a soft landing.”

Maarten Gischler, Senior Water Adviser at Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Netherlands

The Global Commission’s research and quantitative modeling estimate that the future cost of inaction on water could reduce annual GDP by 8% in high-income countries and 12–15% in low- and middle-income countries, potentially amounting to $20–30 trillion per year globally by 2050.

However, these figures likely underestimate the true cost, as they do not capture the long-term impacts of injustice and the negative impacts on our environment. As Joyeeta Gupta, Professor of Environment and Development in the Global South at the University of Amsterdam, explains: “Such modeling is unable to account for many qualitative impacts — for example, the lifetime impacts of a child who misses school because of poor sanitation services or of a woman raped on the way to collect water. The current market system is unable to prioritize recognition and epistemic justice to say nothing about redressing interspecies, intergenerational and intragenerational justice.”

From a macroeconomic perspective, investing in water resilience clearly outweighs the costs of inaction. Yet, at the micro level — whether for farmers, businesses, or households — returns on investment may only materialize in the medium term, creating a strong incentive to delay action. Maarten Gischler raises a critical question: “How do we redress this as long as micro-level incentives and macro risk do not align?” To this, Ovink adds that stronger measures are needed to stabilize the water cycle, with clear linkages between investment and return. Water-cycle stability is the foundation of the entire development agenda.

The action required

“To radically transform both water use and supply requires a shift from siloed and sectoral thinking to an economy-wide approach to the entire water cycle, including both blue and green water.”

Mariana Mazzucato, co-chair of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water

The report outlines five mission areas for coordinated action, spanning local to global scales.

- Food systems: Launch a new revolution in food systems to improve water productivity in agriculture while meeting the nutritional needs of a growing world population.

- Biodiversity and land use: Conserve and restore natural habitats critical to protect green water.

- Circular economy: Establish a circular water economy, including changes in industrial processes.

- A clean-energy, AI-rich and low water-intensive society: Enable a clean-energy and AI-rich era with much lower water intensity.

- Safe water and sanitation for all: Ensure that no child dies from unsafe water by 2030, by securing a reliable supply of potable water and sanitation for underserved communities.

As Mariana Mazzucato explains, “Missions turn policy on its head. Instead of focusing on sectors, technologies or firms, a mission-oriented approach begins by identifying the most pressing societal challenges before breaking them down into manageable policy pathways.” These missions are supported by the Global Commission’s theory of change, including four accelerators — reinventing finance, transformative governance, global data acceleration and multilateral water governance — and three pillars: equity, sustainability, and resilience.

Crucially, these missions must be pursued simultaneously, as success in one depends on progress in others. The Global Commission argues that governments must play a central role in shaping markets and creating enabling environments that support just and equitable transitions. Achieving these missions will demand collective effort across public and private sectors and behavior changes throughout society.

Assembling this complex puzzle is particularly challenging in today’s geopolitical climate — especially for the most vulnerable countries, which face high debt burdens, limited fiscal space, and constrained governmental capacity to influence markets. This raises a critical question: What will it take to make the Global Commission’s recommendations actionable in such contexts?

Where has Global Commission’s policy advice gained traction?

“The five missions outlined in the Global Commission’s report resonate across a broad ecosystem of stakeholders — academics, policy researchers, implementers, and funders alike. The three missions focused on conserving green water, promoting reuse, and advancing the water-energy nexus have generated the most interest.”

Arunabha Ghosh, CEO, Council on Energy, Environment and Water

“The Global Commission on the Economics of Water has provided significant impetus to the policy and financial discussions on economic impacts of climate change, which, first and foremost, as we show in the report, are manifested as abrupt changes in green water flows, precipitation levels and thereby freshwater supply from ‘blue’ surface and sub-surface water sources. This has provided a much-needed input to the wider risk assessment of breaching planetary boundaries.”

Johan Rockström, Director, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research

Since the release of its landmark report, the Global Commission’s ideas have begun to shape policies and practices across international institutions, finance sectors, and corporate partnerships, signaling growing momentum behind its vision for sustainable and just water management.

Feedback has shown that the Global Commission’s framing of the hydrological cycle — linking blue, green, and atmospheric water and connecting across policy domains — has gained significant traction in international and multilateral arenas. For example, the EU Water Resilience Strategy has adopted the re-stabilization of a disrupted water cycle and two of the five missions as core objectives. The World Bank Group’s water strategy follows a similar logic, as do program allocations by the Green Climate Fund and the Asian Development Bank’s water-systems approach. The Global Commission’s recommendations are also reflected in the themes of the 2026 UN Water Conference and have been amplified in the messages delivered by member states and partners at the UN.

The economic risks of inaction are also resonating in the international finance community, prompting new risk-mitigation strategies. An increasing number of corporations are developing water strategies, focusing on production regions facing the highest water-related risks. Coalitions of leading companies are forming, and corporate initiatives to expand water reuse closely align with the Global Commission’s recommendations.

The Global Commission’s call for Just Water Partnerships — including hard caps on water use per basin, based on availability and ecosystem needs — has evolved into a global initiative led by WaterAid with support from IWMI and others. This effort was recently spotlighted at a High-Level Round Table during the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) and at the Global Launch of the Principles for a Just Water Partnership Process.

Where has there been pushback?

“One thing that ten months of debate have made clear is that a global report — and the global process behind it — on water’s role in the economy, and the economy’s influence on water, is a very ambitious and complex undertaking.”

Maarten Gischler, Senior Water Adviser at Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Netherlands

While the Global Commission’s comprehensive framing of the global water cycle has garnered significant support, it has also sparked important debate within the water community. Critics are concerned by the call to govern the hydrological cycle as a global common good. They question whether the Commission’s recommendations strike the right balance between global vision and local realities, are sufficiently actionable, and adequately address the social, political, and justice dimensions of water governance.

Within the blue water community, some express concern that the global framing risks diverting attention and resources away from local water management efforts — efforts that often deliver tangible, short-term results — toward broader global initiatives whose impacts may be less immediate. Others challenge what they see as technocratic solutions to deeply social and political problems, highlighting the report’s limited engagement with power dynamics and its struggle to fully integrate justice considerations into its economic analyses.

A particularly sensitive topic has been the Global Commission’s recommendation that universal access to water service delivery must go hand in hand with generating enough revenue to cover operations, maintenance, and capital costs, through effective pricing, subsidy reform, and performance improvement of service providers. The report acknowledges that existing subsidies disproportionately benefit middle- and high-income households rather than those most in need. Yet, the Global Commission’s proposals regarding pricing and subsidies have ignited fierce debate on compatibility with the human right to water and concerns about commodifying a basic necessity. Critics argue that such measures do not fully align with the principles of recognition and epistemic justice that the report itself champions. As Gupta stresses, “Water justice has to be placed at the center of water governance and water markets. One has to ask: who causes the problem, who suffers, and who benefits.”

The Commission’s suggestions on charging for irrigation water have also met resistance. Many practitioners and researchers find these ideas unrealistic. The Global Commission’s recommendation to encourage more efficient irrigation is also debated: while efficiency gains improve farm productivity (micro level), they tend not to reduce total water use (macro level) and may even increase inequality. Some critics question why the report did not focus more on resilience of rainfed agriculture, which remains the main way many farmers grow crops around the world.

Ovink recognizes these critical points, stemming from decades of hard work and commitment, and stresses that we need to work together to benefit from collective experience, emphasizing: “Water can and must be an organizing principle of our collective work in sustainable development. Let’s find this common ground in a One Water Mission for the world.”

What next?

To continue this journey, it is not enough to simply celebrate the many initiatives sparked by or aligned with the Global Commission report. Delivering results will require perseverance at all levels (local to global), a clear sense of direction regarding the global common good, courageous decision-making locally and globally, and compromise. IWMI, which now hosts the Global Commission Secretariat, can play a role in driving collective thinking and coordinated action beyond the report itself.

The recommendations of the Global Commission can only advance in multi-stakeholder partnerships at different scales. It is important that these partnerships document both their positive and negative lessons and share them in ways others can build on. Conveners, members and partners of the Global Commission, have the opportunity and responsibility to translate recommendations into action, to build coalitions with communities, countries, and regions, starting with platforms for policy and practice where their engagement is strongest. And then learn, adjust and expand from there.

At global level, this includes platforms such as the three Rio Conventions and Ramsar, aiming for strong alignment at the 2026 and 2028 UN Water Conferences. It also includes World Water Week 2025 as a stepping stone. But success at global level must be rooted in tangible progress at the local level. This challenge of matching macro and micro requires a level of interaction, dialogue and collaboration that the Global Commission could not accommodate before completing its report.

This is a work in progress, and the sessions of the Global Commission at World Water Week 2025 represent an important step forward. Your engagement will help advance this effort. Everyone is, in some way, a water manager, and ensuring the stability of the water cycle as a common good requires deliberate, collective action.