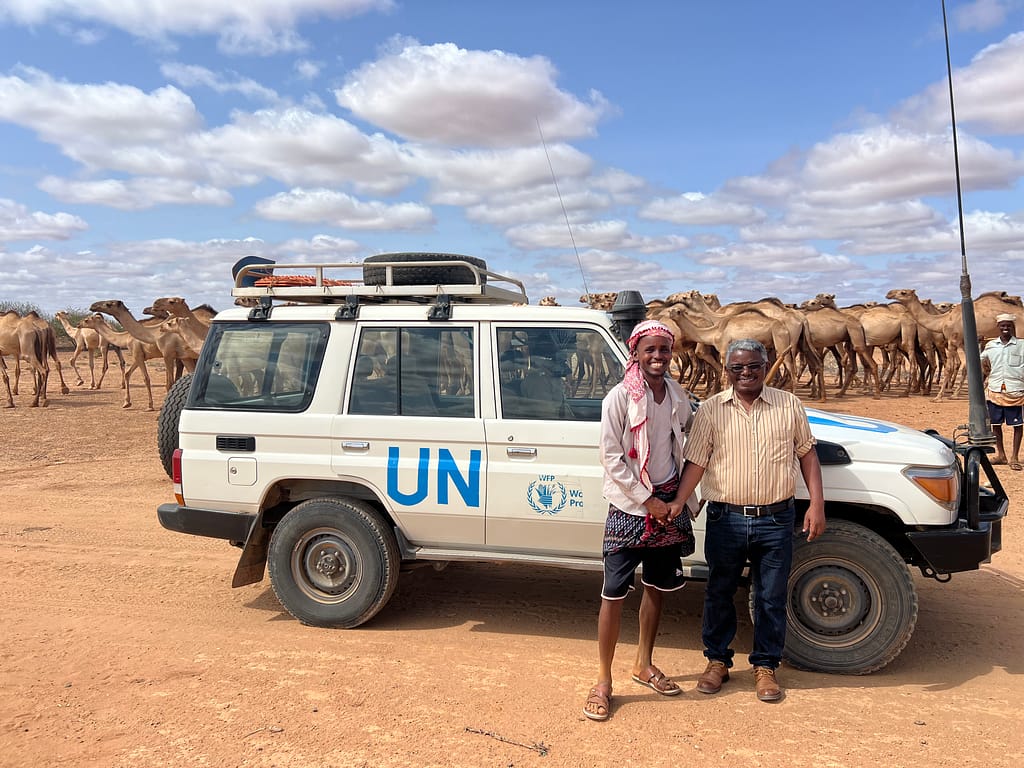

In June, a team from the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and partner organizations arrived in Dolo Ado, a remote district in Ethiopia’s Somali Region. Their objective was to capture drone imagery and river sensor data to build a digital twin of the region’s hydrological system — a virtual model that simulates water flows, forecasts flood risks and supports emergency planning — partnering with the UN World Food Programme (WFP) and the Somali Regional Government to implement and advance our research objectives.

But when the team landed, they were told the drones would not be allowed to fly. From a security perspective, local authorities expressed concerns about the use of drones in the area — concerns the team needed to address before proceeding with flights. The team moved quickly to speak with those authorities, explain the objectives of the fieldwork mission and get verbal approval, meeting with the municipality, the police commissioner and the Ethiopian Defense Forces.

Dolo Ado is one of the largest and most complex humanitarian zones in East Africa. It is home to five refugee camps and a number of surrounding host settlements. Over 219,000 Somali refugees have migrated to the region, most having fled conflict, drought and famine. Shelters are basic — made of tarpaulin, mud and wood — and packed closely together on dry, low-lying ground. Water is scarce. Food rations are distributed monthly, but many families sell part of them to buy other essentials. Health posts are overstretched, and outbreaks of malnutrition and disease are common.

Because Dolo Ado lies at the confluence of the Genale and Dawa rivers, the camps are especially prone to flooding when rain falls upstream in the Ethiopian highlands. Local infrastructure is not built to withstand such extreme weather events, and with climate change, heavy rainfall has become more frequent, leading to flash floods that make life in the camps even harder.

Planning for floods in places like Dolo Ado is both urgent and difficult. Conventional tools — static maps, delayed data — are not enough to respond to rapid changes on the ground. Humanitarian actors need access to real-time risk information to make faster, more targeted decisions: where to relocate shelters, when to evacuate, which roads to reinforce. Without that, communities face recurring disasters with few ways to adapt.

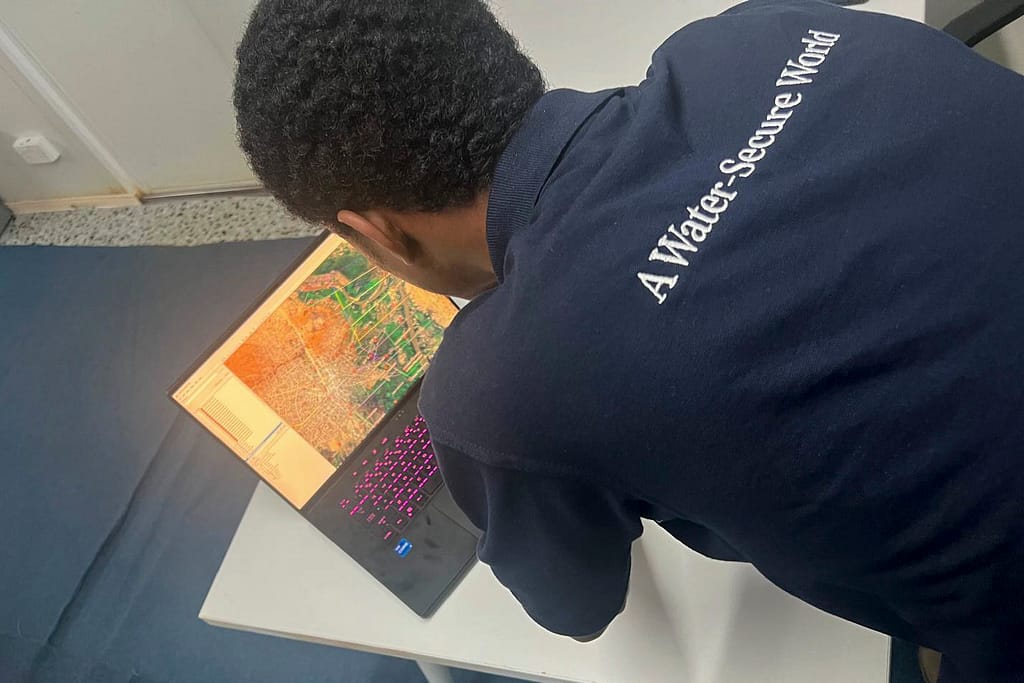

The Dowlada Deeganka Soomaalida Digital Twin, or DDS Digital Twin for short, is designed to change this. Unlike static maps, digital twins update with new data, much more precise than satellite imagery. This IWMI model will also integrate information from a participatory mapping session with community members in 2024, in which residents of the camp helped trace the extent of the 2023 floods using printed basemaps. Now built from drone imagery, river surveys and local knowledge, the digital twin will be a virtual replica of the floodplain. Farmers, community members and government authorities will soon be able to test different scenarios, simulate flood events, and visualize the impact of decisions before acting and investing.

This field mission — part of the CGIAR Food Frontiers and Security Program and the CGIAR Accelerator for Digital Transformation — was focused on collecting the core data needed to build the model. IWMI colleagues, Alemseged Tamiru Haile, Senior Researcher, Mitchell McTough, Postdoctoral Fellow, Elizabeth Wamba, Regional Communications and Knowledge Management Expert, Tilaye Worku, Assistant Researcher and specialist in flood mapping, and Mohammed Abdella, GIS and Remote Sensing Specialist, teamed up with Ousman Belay who is a certified drone pilot.

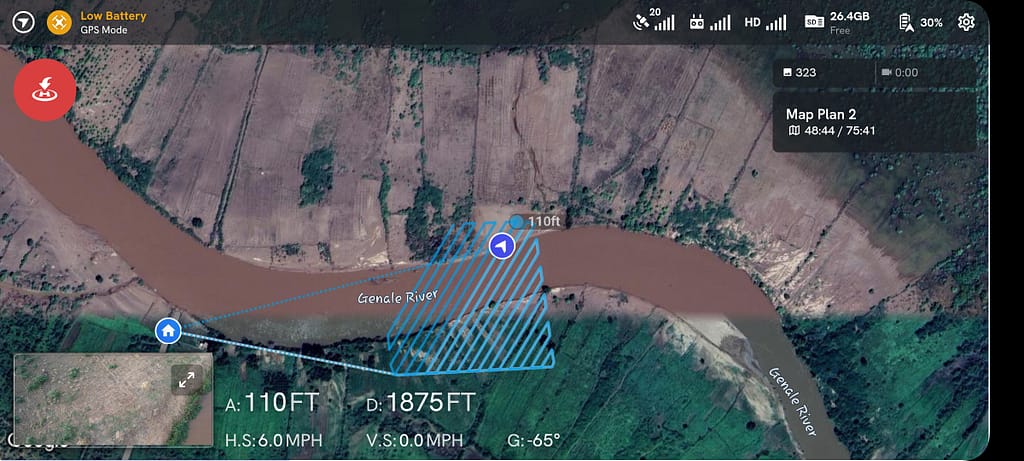

Once in the field, the team ran calibration tests and captured panoramas by the river. Ousman and Mohammed focused on capturing Ground Control Points; a rectangular pad with black and white quadrants was used to align the drone imagery. The drone captured the area where the pad was located, allowing for alignment by matching the pad in the image with its GPS location. These are essential for producing the 3D topographic model that will be a base for the digital twin.

At the same time, Tilaye continued with flood mapping, collecting river cross-sections using a GPS and a sensor mounted on a wooden boat.

“I crossed the river more than 20 times to get enough data. There were crocodiles in the water, which made it risky. Thankfully, at another site, we used a bridge — that made the work much easier,” recollects Tilaye.

It was Mohammed’s first time to fly a drone. “We could never have covered all blocks in 15 days without the support from WFP. They provided vehicles and generators to plug in the drone batteries, which we had to recharge several times a day,” he said.

Mohammed is among the first IWMI researchers to receive a drone piloting training. “I learned a lot to apply these skills in future work,” he concluded proudly. The team is planning additional sessions to expand in-house capacity and accelerate future approvals using IWMI’s institutional permits.

In parallel, the team interviewed local farmers, host community members, government officials and WFP project staff to document experiences, gather insights and better understand community priorities related to flood risk. To improve the flood maps, even more detailed socio-economic data will be needed — including where people live, what assets are at risk and how communities are affected during floods.

Once data collection was completed, the team used specialized software to process the drone imagery and generate high-resolution 3D models of the floodplain. The models will also be used to develop a virtual field trip (VFT) to be posted on the IWMI VFT platform to share the data collection process with partners and show how digital twins can support planning in flood-affected areas.

Bringing tools like digital twin technology to places like Dolo Ado is not just about technology. It is about taking science to where it is most needed, but also the hardest to apply. Fragile settings come with real constraints — limited infrastructure, complex approval processes from local authorities and communities and high security risks. Yet these are the same places where better planning, early warning and informed decision-making can have the greatest impact. This mission showed that it is possible to generate high-quality data, build local capacity and apply scientific methods, even in one of the most remote and exposed regions in the Horn of Africa. The challenge now is to keep going — not only to finish the model in the coming months, but to ensure it is used, adapted and owned by the people it is meant to serve.

This field mission can also serve as proof of concept. With the right tools, training and partnerships, it is possible to generate actionable data in fragile settings. It reflects IWMI’s core approach: developing and testing investible, practical tools that can be scaled and adapted to help communities plan water-related risks in some of the world’s most challenging environments.