Along the Akaki river, which winds through Ethiopia’s bustling capital city of Addis Ababa, over five million people are increasingly exposed to pollutants, which scientists warn could accelerate the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). As waste and wastewater systems buckle under rapid urbanization and population growth, infections that were once easily treated are becoming harder to cure, turning AMR into a growing public health crisis in the city.

AMR occurs when microorganisms like bacteria and viruses evolve resistance genes, allowing them to survive exposure to medicines such as antibiotics and antivirals. When this happens, treatments that once worked become ineffective, and routine infections and minor injuries can turn deadly.

In Ethiopia, regulations around the disposal of medication are weak. Water quality assessments from the Akaki river show that between 0.6-20% of some bacterial groups are resistant to drugs, fuelled by contamination from hospitals, farms and households.

“AMR in Addis Ababa and Akaki catchment leads to hard-to-treat infections, higher mortality and economic burdens,” said Alemtsehay Adem, an officer of the Addis Ababa Health Bureau. “Contaminated water spreads antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Improving water and sanitation is essential to break this cycle.”

Experts stress the need for sustainable technologies and a holistic One Health approach to tackle the rising risk of AMR. One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals and ecosystems. Using the One Health framework can reduce the spread of antimicrobial resistance by coordinating actions across the full spectrum of disease control – from prevention and detection to response and management – ensuring that antibiotics and other medications are used responsibly and safely in all sectors.

Water’s central role in the One Health approach

Water connects human, animal and environmental health. Water transports antimicrobial-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antimicrobial-resistant genes (ARGs) downstream, spreading AMR from sources like hospitals, cities and farms. By improving wastewater management, water quality and infection control across these interconnected systems, One Health helps limit the circulation of resistant microbes in communities, livestock and the environment.

The International Water Management Institute (IWMI) is leading the way in making water a central part of the One Health approach. In Addis Ababa, IWMI partnered with government and research institutions to generate scientific evidence supporting water’s role in national and regional One Health programs.

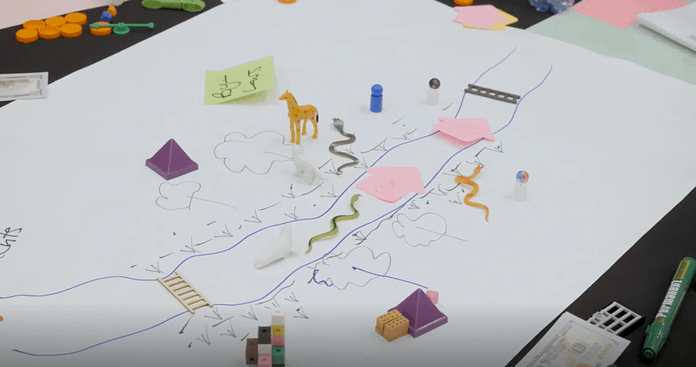

Recognizing the need for practical guidance on the preparation of water pollution control and prevention plans, IWMI hosted a co-design workshop in May 2025, supported by CGIAR’s Sustainable Animal and Aquatic Foods (SAAF) program. The event brought together 28 experts from 10 organizations across water, environment, health and media sectors. Together, they formulated sequential guidelines for pollution control and water quality improvement, emphasizing water’s role as an enabler of One Health.

The guidelines begin with an assessment of the river’s current pollutant pressures and mitigation efforts. The process then calls for mapping existing pollution control programs, setting time-bound water quality goals for specific river sections or whole watersheds and using model simulations to test whether current actions are sufficient. Where gaps remain, officials can then identify and evaluate the most cost-effective solutions. The guidelines also note the importance of securing early buy-in from key authorities, setting realistic plans in alignment with stakeholder goals, backed by evidence-based data.

Defining targets for a cleaner Akaki river

Developing an effective water pollution prevention plan starts with setting clear, time-bound goals. For the Akaki river basin, stakeholders from the river pollution control authorities, researchers and community representatives have agreed on a 10-year vision. The goal is to enhance the Akaki river’s ecological integrity through the One Health approach by reducing pollution and supporting sustainable irrigation and recreational practices. By most water quality measurements in the Akaki river, pollutant levels exceed safe thresholds by a significant amount. While several priority actions for water quality and pollution reduction have been identified, further alignment with development plans is needed. Defining acceptable water quality standards and the maximum pollution load the river can handle will be key steps for future planning.

A new direction for Akaki river pollution control

Despite recent investments in wastewater treatment and river restoration, experts warn that weak data systems and fragmented planning continue to undermine pollution control in Addis Ababa. During the co-design workshop, pollution control experts reviewed river corridor development and wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in the city.

Experts noted that major challenges persist, though there has been progress through efforts to clean rivers, build WWTPs capable of daily treatment of 100,000 cubic meters of wastewater and improve drainage in older neighborhoods. They highlighted that integrated planning was difficult due to limited access to geoinformation and inconsistent datasets. Experts identified data sharing as a priority action, noting information gaps in addressing pollution from hospitals, industries and livestock. They cautioned that existing government plans may fall short of achieving the desired water quality targets in the set time frame.

Real progress will require clear water quality objectives, better modeling of existing solutions and coordinated efforts among One Health programs and local water networks such as the Addis Ababa Water Governance Network.

“Engaging stakeholders from all sectors is essential for creating river pollution control plans that are practical, inclusive and sustainable,” said Lakech Haile, an ecosystem and biodiversity researcher at the Environmental Protection Agency of the Addis Ababa City Administration. “By bringing together diverse voices and expertise, we ensure solutions that truly protect our rivers and communities.”

The new pollution control guidelines for the Akaki river catchment set clear actionable goals, integrate stakeholder input and test the effectiveness of existing pollution control initiatives. With these steps, officials now have a practical strategy with key stakeholder buy-in, to curb AMR pollution and strengthen One Health outcomes in Ethiopia’s capital city of Addis Ababa.