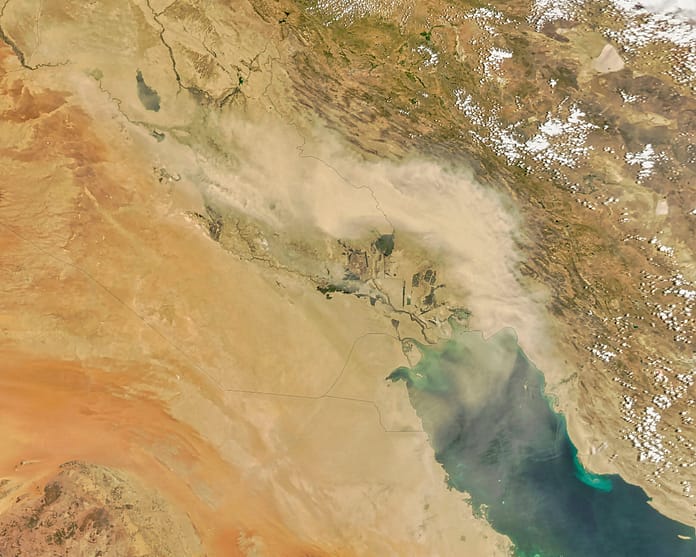

Iraq’s rivers once nurtured some of the first civilizations of our world. As early as 12,500 years ago, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers fed fertile farmlands and sustained the great Mesopotamian Marshlands. Today, however, Iraq is facing one of the most acute water crises in the Middle East. Years of conflict, population growth and climate stress have taken a toll. Droughts are intensifying, salinity levels are rising, and farmers are struggling to irrigate their fields.

Amidst these seemingly insurmountable challenges lies an opportunity. By turning to nature-based solutions Iraq can restore ecosystems, strengthen its agricultural sector and help communities adapt to an uncertain climate future. Such approaches harness nature to deliver not only environmental benefits but also social and economic gains for livelihoods.

The International Water Management Institute (IWMI) is working with local communities, government partners and international collaborators in Iraq to demonstrate how nature-based solutions like constructed wetlands can transform wastewater from a liability into a resource. This requires integrating technical solutions with social and policy innovations to ensure these approaches can be scaled to create lasting impact.

Community at the center

For decades, water management in Iraq has been dominated by centralized systems. But central systems are often costly, energy-intensive and vulnerable to breakdown. To be sustainable, nature-based solutions must be owned and managed by those who depend on them most: local communities.

When communities and Water User Associations (WUAs) are empowered to take the lead, water systems are not only better maintained but also more trusted. For example, the Maysan Constructed Wetland, funded and implemented by the World Food Program, created a locally led and cost-effective wastewater treatment solution by using a participatory governance strategy inclusive of farmers, households and local authorities.

IWMI stepped in to design and roll out the community engagement framework and governance structures that empowered locals to lead. IWMI came on board to design and roll out the community engagement framework and governance structures that empowered locals to lead. This strategic focus on institutional capacity ensures the bottom-up approach fosters deep ownership, builds robust confidence and guarantees that the wetland’s operation continues long after the project’s completion.

Scaling beyond pilots

While pilots like the Maysan project are promising, Iraq’s water challenges demand solutions at scale. Expanding nature-based solutions requires a multi-pronged strategy.

The first step to scaling requires updating water quality standards through a shift to tiered, risk-based standards for irrigation water. This is essential to move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach that currently limits reuse. Standardized water quality that aligns with global best practices ensures the protection of public health — making the most of every drop.

Second, engaging the private sector is critical, as scaling nature-based solutions is not possible through public funding alone. Investments from agribusinesses, technology providers and other private actors can drive adoption and innovation, particularly when the solutions are shown to be both sustainable and profitable.

Finally, targeting priority regions — specifically the central and southern provinces of Basrah, Maysan Muthanna and Thi-Qar — is urgent. In these regions, water scarcity and salinity are most severe, and farmers are already informally reusing wastewater to survive. Focusing on high-value crops such as wheat, potatoes, dates and fruits, along with salinity-tolerant crops like barley, can provide both economic incentives and climate resilience. Greenhouse cultivation offers another pathway for maximizing productivity under water stress.

Challenges on the ground

IWMI’s readiness assessment shed light on the most urgent challenges that need to be overcome to scale nature-based solutions for reclaimed water reuse in Iraq.

The frequent and inefficient operation of centralized wastewater treatment plants pose a significant technical challenge. In contrast, constructed wetlands offer a low-cost, electricity-independent alternative that can be managed locally. They mimic natural processes, using plants, soils and microbial communities to filter and treat wastewater without relying on energy-intensive machinery or complex chemical inputs.

Farmers are hesitant to adopt modern techniques due to high costs, unreliable power and risk aversion. With current irrigation systems running at 30-40% efficiency, these agricultural barriers are significant. However, there is an opportunity to reverse inefficacies using modern irrigation, with its potential to double yields — and significantly increase a farmer’s return on investment.

In one of the world’s most important wetlands — the Mesopotamian Marshlands — environmental pressures are rising. Upstream damming, chronic water scarcity and pollution are intensifying stress on the marshlands. While treated wastewater can support their restoration, long-term monitoring of soil salinity, sodium levels and nutrient balances will be critical.

On an encouraging note, social dynamics indicate that communities are increasingly aware of the water crisis and are open to reuse, especially when they see economic benefits. Farmers who witness higher yields and profits from improved practices become strong advocates for change. This is why the role of Community of Practice (CoP) platforms is critical. This approach was successfully applied in Maysan. By bringing farmers, officials and researchers to the same table, such platforms create the trust and collaboration needed to move from isolated pilots to systemic change.

Building a resilient future

Nature-based solutions alone cannot solve Iraq’s water crisis. Integrated into a broader national strategy, they hold transformative potential, including restoring ecosystems like the Mesopotamian Marshlands, boosting agricultural productivity in high-value crop zones, and empowering communities to manage water more sustainably.

The experience from Maysan shows that collaboration among scientists, governance actors and communities can transform nature-based solutions from small-scale pilots into policy impact. With stronger institutions, clear water quality standards and private sector engagement, these solutions can be scaled across Iraq’s diverse agro-climatic zones.

Iraq’s water crisis is not only a challenge, but also an opportunity: to reimagine water management, to empower farmers with innovative tools and to restore ecosystems that sustain life and livelihoods. By scaling such solutions and embedding them in policy, Iraq can turn the tide — moving from crisis management to building a resilient and sustainable water future for generations to come.