In the early morning of September 11, 2023, two major dams gave way in northeastern Libya, flooding the coastal city of Derna. The flooding was triggered by Storm Daniel, a cyclone that came across the Mediterranean and hammered northeastern Libya with 150-240 mm of rainfall. Water quickly rose in the Wadi Bu Mansour Dam and the Sadd al-Bilad Dam overnight, weakening their structures and unleashing over 30 million cubic meters upon the city below, sweeping away buildings, bridges and people to the sea.

Thousands of deaths — estimates range from 11,000 to 24,000 casualties — and mass displacement ensued. Almost two years after the disaster, Derna is still reeling and key water and sanitation infrastructure remains damaged, preventing sufficient water access and endangering public health.

As Libya contends with the impacts of the catastrophe, lessons and opportunities for action unfold for aging dams and water management elsewhere, particularly in conflict-ridden areas.

The rise and fall of the Big Dam Era

Dams serve many purposes: hydroelectricity, irrigation, water management. Dams are a form of grey infrastructure, meaning human-built systems for managing water, as opposed to green infrastructure, which integrates natural systems for water management, also known as nature-based solutions.

Dams often alter the landscape within which they are built, causing habitat destruction through flooding and alteration of the natural flow of waterways, threatening native species. The productive capacity of dams also diminishes over time as sedimentation builds.

The 1970s marked a boom in dam construction across Asia and Africa. The so-called “dam revolution” of the 20th century enabled agricultural expansion and economic growth, particularly for arid regions, but simultaneously displaced communities and disrupted ecosystems.

Today, dams are not seen as the silver bullet they once were for economic development or poverty reduction. Combined with the comparable affordability of wind and solar energy, the construction of big dams has slowed globally. However, policymakers everywhere must continue to contend with existing dams and their upkeep.

The Wadi Bu Mansour Dam and the Sadd al-Bilad Dam were built in the 1970s to fulfill local water management needs: irrigation for agriculture, water access for nearby communities and flood control. However, as the Derna District faced conflict and political mismanagement, infrastructure was disregarded for decades and without maintenance became increasingly vulnerable to environmental disaster.

Solutions for addressing older dams include decommissioning or integration with green infrastructure. Decommissioning, partially or entirely removing a dam, can help guarantee public safety in the face of disaster and is often less expensive than maintenance costs. However, aging dams often still serve water access purposes, so for communities that rely upon dams that are not at risk of collapse, integration is a compelling route for sustaining their existence. Integration involves practices such as reforestation along dams to reduce erosion or releasing downstream flow to sustain ecosystems.

Yet for regions impacted by conflict such as Derna, these time and resource-heavy water management plans can be difficult to attain.

Conflict and climate change in Derna

For decades, Derna has been a space of economic exclusion and major conflict as rival political stakeholders vie for command. As a result of continuous instability, the clay and rock dams were neglected and became cracked and eroded.

Conflict even made repair records unclear: the last known repairs are believed to have taken place in 2002, though some reports suggest no work was carried out after 1983. Attempts at dam repairs were sidelined in 2011 due to missing funds and unsafe conditions for construction teams.

Climate change compounded these political challenges setting the stage for the Derna dams’ collapse. World Weather Attribution conducted an analysis of Storm Daniel and found that climate change increased the likelihood of torrential rains by 50% — a reflection of a globally disturbed hydrological cycle and increasingly frequent and intense major storms.

Additionally, climate change altered the landscape of Derna, hardening the land and reducing the absorbency for runoff water. Many dams were built in an era before engineers accounted for the threat of climate change and are not designed to hold up against such extreme rainfall.

Aging dams: a global issue

Officials in Libya may have ignored important warning signs — however, similar red flags are waving elsewhere. The Derna catastrophe turned attention to dams in other countries and their growing stack of concerns.

As of 2021, tens of thousands of large dams around the world had surpassed 50 years, the “alert” age threshold. Across Asia, Africa and Northern America sit dams at risk of collapse. Between India and China alone are 28,000 dams built in the mid-twentieth century, while dams in the U.S. have an average age of 65 years.

It can take years to decommission dams, but as the risks of disregarding large and deteriorating dams become more apparent, policymakers need to fast-track protocols to remove or repair aging dams.

Water as a means of conflict resolution

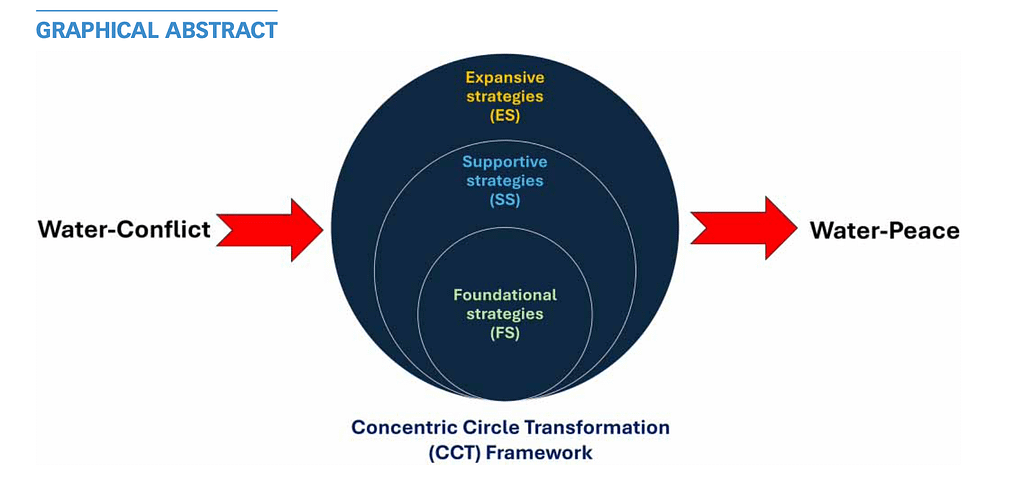

Yet such protocols are complicated to enact in areas of conflict. In the arid and water-scarce Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, research from the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) revealed an increase in water-related disputes, with water acting as a “casualty, a weapon and a trigger for violence.” In response, IWMI researchers advocate for water as an opportunity for peace and conflict resolution through the Concentric Circle Transformation (CCT) framework.

According to Maha Al-Zu’bi, a regional researcher at IWMI who developed the CCT framework, the transformation “starts with governance and trust at the foundational level, then adds the supportive layer of infrastructure and early-warning systems, and finally builds out the expansive layer of cooperation, innovation and awareness. Together, these tiers link social legitimacy with technical fixes, making water security more durable.”

CCT can be envisioned in flood and dam management planning as a way to lessen the vulnerabilities that often lead to water-related conflicts. As CCT co-author Muhammad Khalifa explains, “Hard interventions for ageing dams in vulnerable regions concentrate on resilient infrastructure, repair and monitoring. Soft interventions improve international support, community readiness and governance. Connecting the two guarantees that repairs are a component of a larger system that reduces risks in the future rather than only being technical solutions.”

For aging dam management in conflict zones, there is not one singular approach. However, the CCT framework allows communities to shape their own water management plans. Al-Zu’bi adds, “With CCT, dams move from being fragile points of conflict to shared assets for resilience.”

Aging dams are an urgent problem across nearly every continent and need to take a central place in water storage infrastructure management, even when conflict poses a seemingly insurmountable challenge to implementation. If dams are left to age without maintenance, the risk of a repeat crisis such as the Derna dam collapses increases. Integrated intervention strategies provide a guide forward for both water security and conflict de-escalation.