People in refugee settlements often live alongside local communities that are already coping with limited resources. These settlements are often in dry land and environments that face erratic rainfall, poor soil and low vegetation cover — presenting their own fragility as ecological areas. When displaced families arrive, they draw on the same land, water and energy. As these shared resources come under pressure, implementing practices that foster sustainability while building social cohesion is critical for long-term development.

A recent webinar of the International Water Management Institute’s (IWMI) “Frontlines Learning Exchange (FLEX)” series spotlighted youth and women-led circular innovations in fragile contexts, discussing how such approaches transform the way practitioners collaborate and support refugee communities.

The FLEX webinars aim to promote knowledge-sharing between IWMI researchers and partners navigating complex challenges. Among the voices shaping the discussion was Mary Njenga, a senior research scientist in bioenergy, leading refugee-centered programs at the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF). Through her experiences, several practical lessons emerge — ones that can inform future projects working with refugees and displaced communities.

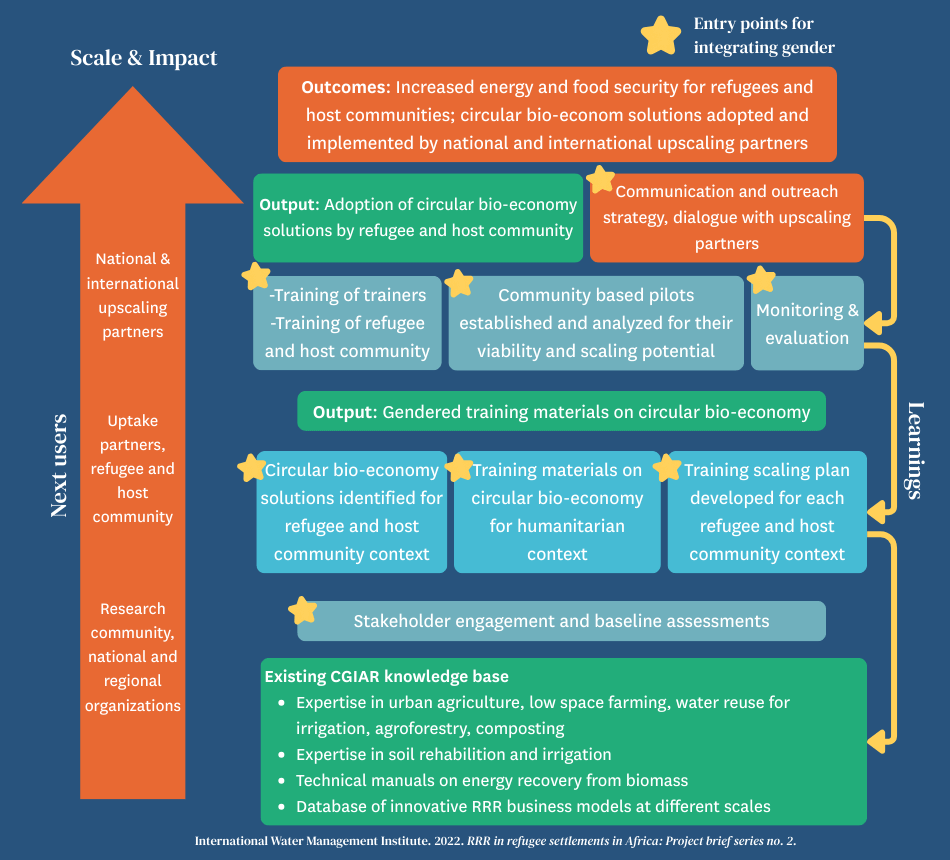

The Gender Responsive Resource Recovery and Reuse (RRR) in Refugee Settings in Africa project, co-led by IWMI and CIFOR-ICRAF, worked across six refugee camps and their surrounding host communities in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda. The project aimed to establish a circular bioeconomy that can support sustainable agriculture and cleaner energy, with women’s needs and experiences at the center.

Women and youth make up much of the population in the refugee camp settlements, and many women shoulder the bulk of caregiving. Therefore, it was key that the project centered on women learning sustainable skills to transfer throughout their community.

In practice, this meant women learned to grow food at home, plant trees alongside crops and use sustainable cooking methods in arid land. The RRR method focused on techniques that families could use immediately at home, like building stoves from local clay and making fuel briquettes from leftover organic material and biomass in the surrounding area. With these additional skills, opportunities to earn an income through small-scale urban agriculture can open, creating avenues that allow for more growth and long-term residence on the land. These shifts help strengthen food security and energy resilience for both refugees and host communities.

“It is important that communities can reliably access seeds and planting materials, whether for vegetables or for trees, and we work to ensure they have these resources within their own systems,” said Njenga. “That’s why we do quite a bit of training. For example, if you grow indigenous vegetables and integrate fruit trees in your compound, how can you also produce your own seeds and seedlings? It’s about building capacity that lasts for resilient food, energy and green jobs.”

Tailoring training to local realities for sustainable impact

To ensure the community is positively impacted far beyond the duration of the project, it was essential to understand the local realities of the families living in the refugee settlements and neighboring villages. This meant taking the time to understand who these communities are, and how age, gender and daily responsibilities should shape the way training was designed and delivered.

This clarity helps practitioners determine not only how to train, but also who to train. In refugee settlements, this means materials need to be adapted to several nationalities with a mix of cultures and languages, in an ecosystem that is within the people’s culture and needs. A strong gendered perspective needs to be maintained at every stage to ensure no one is left behind.

In already fragile environments, capacity development works best when scientists train local champions who can continue training and technical support within their community. This training must include both people living in refugee camps and neighboring communities to ensure that knowledge is carried forward, allowing capacity to grow rather than disappear.

“Efforts to include both communities flips the idea of refugees being seen as a problem to possibly part of the solution,” said Njenga.

Meaningful outreach and collaboration improve relationships between neighboring communities and people living in refugee settlements over time. For example, creating employment opportunities for locals in refugee settlements and engaging them in capacity-building projects can decrease the divide between these two communities.

Shifting towards a development approach

As some refugee settlements that may have been intended as temporary turn into more permanent settlements, integrating neighboring and refugee populations becomes increasingly essential.

Kakuma in Kenya, one of Africa’s largest refugee settlements, illustrates how this shift can be positive for both groups. In 2025, Kakuma was officially redesignated as a municipality — part of a broader effort to transform the settlement from a temporary camp into a self-sustaining town.

That transformation matters. By loosening the lines between “camp” and “community,” Kakuma opens the door to economic integration, local governance and more stable livelihoods. As long-term developments become reality, meeting these evolving needs requires better urban planning for the settlements alongside short-term humanitarian responses.

These lessons reflect a shift in how practitioners can approach work in displacement settings — from supporting people as they heal from trauma to building livelihoods and protecting the environment.

When projects integrate local communities, plan for long-term development, invest in local capacity building and adapt to the realities of diverse demographics, they can create people-centered dynamics that foster sustainability and inclusion.