Water resilience remains a critical dimension of climate mitigation and adaptation, furthered by increasing demands for water resources in societies across the world. Interventions to protect water security, however, require sufficient funding flows to be properly designed, implemented, maintained and monitored.

A recent International Water Management Institute (IWMI) publication shows that increased recognition of and support for private climate finance measures, particularly in more localized contexts, can help to alleviate some of the most prominent public funding issues.

IWMI Research Group Leader for Climate Policies, Finance and Processes, Darshini Ravindranath, co-wrote a Position Paper with Paul Steele, the Chief Economist in Shaping Sustainable Markets at the International Institute for Environment and Development. The paper titled “Water Financing: Scaling up Finance to the Water, Energy, Food and Environment (WEFE) Nexus” highlights how climate finance mechanisms can be improved for water security.

New approaches to climate and water financing

Drawing from a vast array of sources and organizational insights, the paper outlines the critical need for water-resilient infrastructure, as over 3.2 billion people now live in severely water-insecure areas. Despite this urgent need, recent estimates demonstrate that only 3%-8% of climate finance goes to water initiatives. Most funding for water infrastructure comes from the public sector. Furthermore, current private financing measures are often disproportionately distributed globally, with only 6% being mobilized in lower-income countries.

Despite their relatively small share of overall contributions, the private sector and regional financing play a vital and often unseen role in the expansion of water infrastructure. Private “Own Source” and Small Medium Scale Enterprises (SMSEs) help to fund irrigation, sanitation and small-scale hydroelectric power. Blended finance measures that combine both public and private finance offer another avenue for tackling barriers to effective water resource management and funding. Furthermore, innovative financial incentives like “water credits” may offer opportunities for increases in private funding flows to water initiatives.

The paper takes an evidence-based approach to identifying pressing barriers and issues surrounding water, food, and ecological systems while informing mechanisms to improve the effectiveness of climate funding flows. It provides a number of recommendations for improving water finance across the world. A stronger focus on and recognition of local and regional water financing is an urgent priority. More concrete incentives and regulations for private and localized water markets would support the continued growth of water-resilient infrastructure. Additionally, a systemic reframing of water as both a mitigation and adaptation asset would expand the opportunities to integrate water financing across sectors.

Global climate finance, previous agreements and developments at COP30

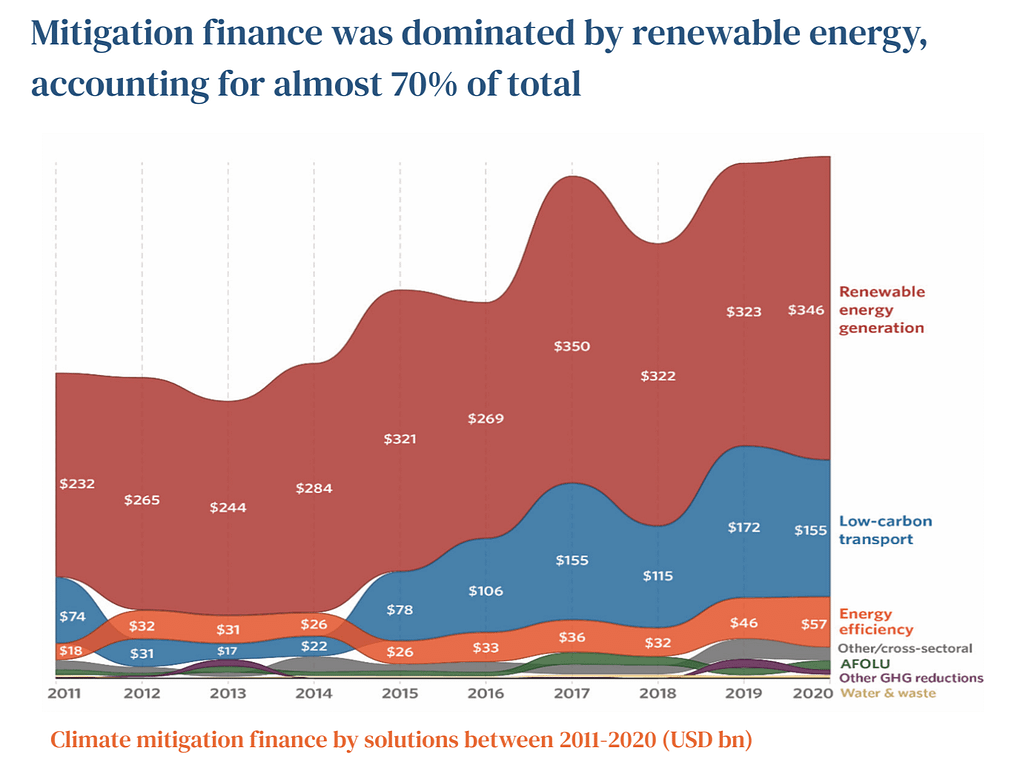

Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement recognized the importance of effective climate finance mechanisms in implementing sustainable development measures. Initial funding targets aimed for $100 billion in contributions per year to enact climate mitigation and adaptation initiatives. However, global environmental research increasingly indicated that finance targets needed to be greatly increased to adequately combat growing environmental risks, particularly in developing countries. Estimates for climate finance needs often exceed $2 trillion per year, with at least $200 billion per year dedicated to water security alone.

To address this gap, COP29 negotiations settled on a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) of at least $300 billion per year by 2035 for climate resilient measures, primarily led by developed countries, while calling upon countries to scale up efforts to reach $1.3 trillion per year by 2035. Despite these heightened targets, few concrete mechanisms have been identified to mobilize these finances. In anticipation of COP30, the presidencies of COP29 and COP30 jointly published the Baku to Belém Roadmap, which highlighted specific finance pathways to reach the $1.3 trillion goal by “replenishing, rebalancing, rechanneling, revamping and reshaping” new and existing measures.

November’s COP30 brought the lens of implementation into focus. The negotiations of COP30 expanded previous efforts but also had key vulnerabilities. The improved Global Goal on Adaptation included clear metrics surrounding water management and resilience, inviting further targeted investment in these areas. The adopted “Global Mutirão” framework called for the tripling of adaptation finance globally by 2035, providing further support for water security initiatives. Despite these gains, specific and measurable pathways to water resilience remain nebulous, and many of these regulations and climate finance increases are framed as voluntary.

Barriers to global climate finance

These funding promises are necessary to achieve long-term water security in the face of increasingly severe climate impacts. Yet significant barriers have hindered efforts to turn these commitments into equitable, sustainable action for communities across the world. Despite the urgent need to implement these finance flows, finance commitments remain voluntary and nebulous, with little well-defined information on countries’ responsibilities or concrete pathways to implementation. Water resilience needs in financing are often absorbed under the generalized banner of “climate adaptation,” leading to difficulties in channeling investments to targeted water resilience interventions across the global stage.

Furthermore, concerns remain around the equitable implementation and impacts of these measures. Over the past decade, only 2.8% of global climate finance supported just transitions. Furthermore, loans requiring repayment, particularly to middle-income countries, were the largest category of mobilized climate finance in 2022. These characteristics of global climate funding flows raise important questions about the recipients and implementation mechanisms of climate finance. Even when sufficient funds are mobilized, implementation issues such as fragmented governance, limited monitoring and evaluation, and insufficient technical knowledge hinder the effectiveness of financed initiatives.

These pressing barriers require ambitious, evidence-based solutions and strategies to overcome them, like those recommended in “Water Financing: Scaling up Finance to the Water, Energy, Food and Environment (WEFE) Nexus”. In light of COP30’s push for stronger implementation, innovative approaches to water management provide key future pathways to water resilience, as well as climate mitigation and adaptation more broadly.