Agriculture accounts for about 22% of total greenhouse gas emissions. Reducing fossil fuel consumption on farms is therefore a non-negotiable priority for mitigating climate change. In Nepal, diesel use contributes to 76% of the total energy consumption in the agriculture sector. Most of this consumption occurs in the Terai–Southern plains, via diesel-based pump sets used to lift groundwater for irrigation. With the electric grid expansion in recent years, fossil fuel consumption is gradually decreasing, but solar power only contributes a paltry 0.51% to the total energy consumption in fields.

Since 2016, a subsidy scheme launched by the Nepal government has supported one and two horsepower (HP) solar irrigation pumps (SIPs) – but demand for subsidized units outstrips supply by ten-fold, and high up-front costs and the limited budget of the subsidy program have stalled wider uptake.

Although Nepal and neighboring Bihar, a state in eastern India, share a border, agro-cultural contexts, climate and groundwater conditions, and even though both countries began solar-pump programs in the 2010s, differing policies and institutions have led to divergent outcomes.

What makes Bihar’s model scalable?

Nepal’s one to two HP SIP systems irrigate between 0.67 and 1.036 Hectares (Ha) and are limited to self-use for farmers. Such a model restricts the economic potential of the pump systems. Bihar’s contrasting entrepreneurial approach provides valuable insights why.

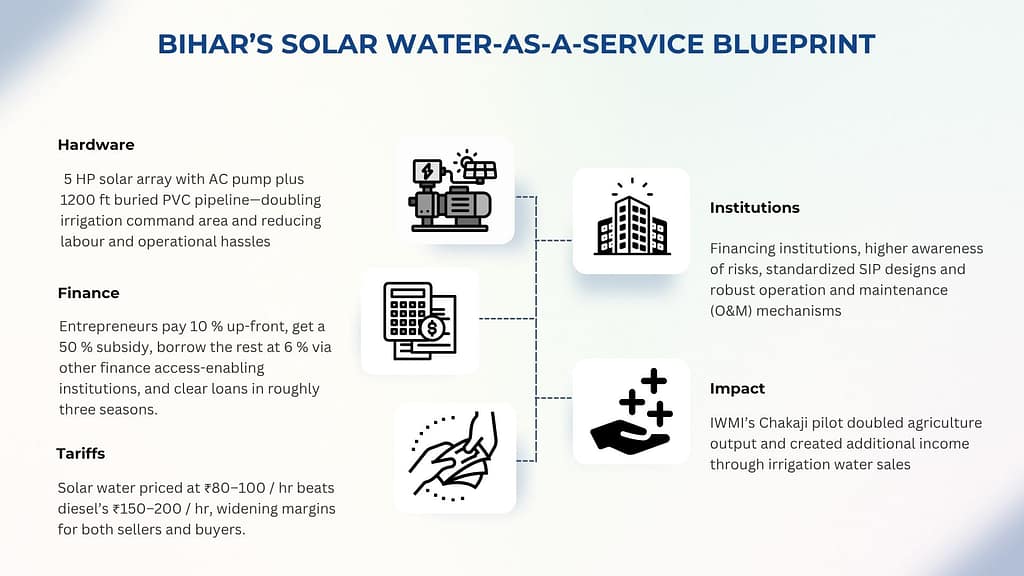

With five HP SIPs, Bihar’s model allows entrepreneurs to sell surplus water to nearby farms and earn additional income. An underground PVC pipeline network (1,000-1,200 ft with multiple outlets) lets entrepreneurs serve neighboring farms without daily re-connection issues, reducing labour and operational hassles, and doubling the command area. Other water buyers also tap into these outlets via foldable pipes.

A SIP entrepreneur in Bihar explained, that “This (distribution network) frees us from the hassle of having to connect and disconnect pipes to cater to neighboring fields.”

The SIP-based water tariffs — Indian rupees (INR) 80-100/$0.92-1.16 per hour — undercut diesel pumps — INR 150-200/$1.73-2.31 per hour — providing a competitive advantage. They charge either hourly or per-acre rates, adapting to customers’ preferences.

Additionally, the SIPs in Bihar are more robust, with lower maintenance costs and lifespans exceeding ten years compared to lower lifespans of SIPs in Nepal. The five HP SIP system comes with an alternating current pump that is able to use grid electricity. Grid integration has enabled the SIP owners to service a larger command area, particularly in peak demand seasons.

With a 50% subsidy and the balance often financed at 6% through government programs, loans are repaid within two to three years via water-sales revenue.

Many of the entrepreneurs in Bihar are women who benefit from strong institutional support through self-help groups, Primary Level Federations and Cluster Level Federations. This has helped farmers to have better access to finance, resources and knowledge, strengthen collective bargaining power and reduce transaction costs. These institutional arrangements, combined with the support from governmental initiatives to alleviate poverty, are instrumental in the success of the project. This arrangement motivates SIP owners to repay the loan, as defaulting can damage social standing and limit future support.

Access to affordable irrigation has led to increases in cropping intensity, diversification towards high-value vegetable crops, and a rise in fodder cultivation and livestock productivity among both SIP entrepreneurs and water buyers. IWMI’s pilot in Chakaji, Bihar that targeted SIP interventions have doubled the agricultural output in the village.

How can Bihar’s model be tailored to Nepal’s context?

Bihar’s water-as-a-service approach could suit Nepal’s dense Terai farms with active diesel markets. But pilots must align with Nepali governance as well as social and institutional contexts, with a bottom-up approach to test scalability and policy recommendations.

Based on their experiences and findings, the IWMI researchers recommend that initial pilots focus on regions where government subsidies and grid access have not yet reached. Similarly, converting existing diesel-pump operators into SIP entrepreneurs can smoothen the energy transition and reduce emissions.

Replicating governance mechanisms like Bihar’s self-help groups and federations is critical for accountability, loan repayment, and effective SIP use. Bihar’s farmers exhibit stronger financial literacy and collective trust than typical Terai growers — highlighting the need for capacity building in addition to governance reforms in Nepal.

Nepali farmers also face deeper structural challenges: limited market access, weak agricultural value chains, fertilizer shortages, poor seed quality and delayed payments. Addressing these barriers is vital for the success of SIP-based entrepreneurship.

High upfront costs deter marginal farmers. Alternative subsidy arrangements, affordable credits, standardized SIP designs, and robust operation and maintenance mechanisms will encourage buy-in and extend equipment lifespan.

Bulk procurement and cluster-based installations can reduce service costs and improve efficiency. Encouraging farmers to invest in SIP infrastructure will foster ownership and commitment, boosting the model’s long-term success. As groundwater irrigation expands, parallel efforts to monitor use and promote efficient practices will also be vital for long-term sustainability.

To accomplish scaling of solar irrigation in Nepal will thus require strengthening governance, deploying robust SIPs, facilitating finance, encouraging farmer investment and building local government capacity. By leveraging lessons from Bihar’s successful water entrepreneurship model, Nepal can effectively integrate solar irrigation with the grid into mitigation pathways. This model can also advance gender equality by empowering women farmers and entrepreneurs by placing a strategic focus on women and marginalized farmers as beneficiaries.